“He’s a good buck for the area.”

My guess is you have heard this phrase many times and may have even said it yourself. It’s a well-intentioned congratulatory statement to someone who has taken an exceptional buck, but it carries a less than exemplary accolade. What’s often implied when we say a buck is good “for the area” is that he’s as big as bucks get in our locale but not as big as he could have been elsewhere.

I think it’s time we stop using phrases like this to qualify our deer and instead embrace our local deer herds for what they are. To do this, I want to share a tale of three whitetail bucks.

Three Bucks

First, it’s important to stress that these bucks represent the same species but exemplify some of the variation in skeletal and antler development across the whitetail’s range.¬†

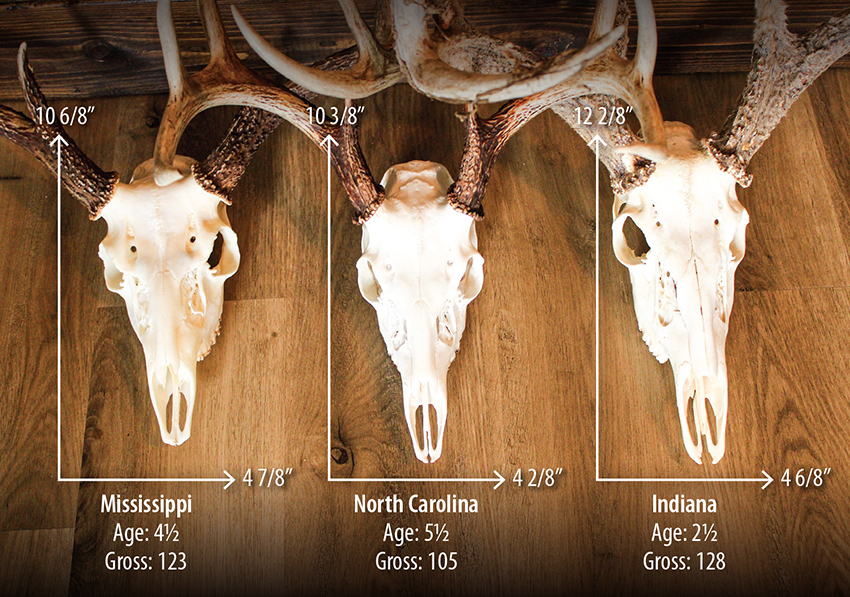

Buck No. 1 (starting on the left in the photo above and in the infographic below) was harvested in the Black Prairie region of central Mississippi, buck No. 2 came from the Coastal Plain of eastern North Carolina, and buck No. 3 is from the Dearborn Upland of southeastern Indiana. I mention the geographic regions because that is far more impactful on how big a whitetail can grow than simply the state of origin. All three states have regions known for producing Boone & Crockett deer and still other regions that commonly produce smaller deer. These are examples from a few of the more extreme regions within these states.

You’ll notice immediately how different the antler sizes are among these three bucks, but if you look even closer, you’ll also notice that skull size varies widely. To capture this variation, I include a few measurements from each buck including gross Boone & Crockett score, total skull length from the back of the brain cavity to the tip of the nose, and skull width at the widest point across the eye sockets.

The most impactful comparison here is between the antlers of the 5-year-old North Carolina buck with the substantially larger antlers from the 2-yr-old Indiana buck. In fact, based off scientifically valid antler-growth curves, the Indiana buck was exhibiting about 60% of his antler potential when he died, meaning he realistically could have grown into a 200-plus inch buck by the time he was the same age as the North Carolina buck!

At this point you’re probably wondering, “Why are these bucks so different in size?” The short answer is habitat quality. You see, these deer lived their lives on three vastly different nutritional planes, and they all experienced some level of nutritional stress that limited their ability to express their full potential, but these limitations were not equal across the three.

Three Regions

The buck from Mississippi lived his life in the Black Prairie region, a fertile crescent of alkaline soils that historically supported a diverse prairie system. This region now has a heavy agricultural component, and the local area where this buck was taken sits on the edge of a large agricultural community. There are some planted loblolly pine forests and reclaimed prairies intermixed with diverse bottomland forests. The understory of these forests produces a variety of high-quality forbs, and the long growing seasons mixed with fertile soils make this landscape feel almost like a jungle of green. However, even in this productive landscape, there are nutritional constraints for deer. Forest thinning and other disturbance factors are limited, leaving deer to compete for the best habitat.

These bucks were, after all, products of their environments, as nutritional limitations regulate what body size is optimal for the landscape and how many resources can be invested into secondary sexual characteristics, aka antlers.

The North Carolina buck came from the southeast corner of the state’s Coastal Plain, living his life just a few miles from the Atlantic Ocean. The landscape he called home is predominantly pond pine pocosins (a type of upland swamp) or mixed longleaf pine stands. Agriculture is limited, and the dominant understory vegetation is waxy-leaved species like yaupon, blueberries and gallberry. In fact, in the moments leading up to my shot at this buck I observed him repeatedly taking bites of gallberry leaves and fruits. In this landscape, green vegetation is never lacking, but high-quality deer forages are somewhat limited due to the abundance of less palatable shrubs. While there is plenty of “okay” food, the nutritional constraints placed on a deer are great.

In the southeast corner of Indiana lies the Dearborn Upland. This region is characterized by moderately glaciated soils with defined topographical features. There is agricultural production primarily found on the flattened ridgetops, but the landscape is still dominated by expansive upland hardwood forests. This interspersion of permanent cover with agricultural openings makes the area especially conducive to whitetails, much more so than more agriculture-dominated regions of central Indiana or the greater Midwest. These forests, when managed appropriately, provide a plethora of forages for deer, holding them over through the winter months when agricultural crops are not available. As is often the case, closed canopy forests limit the availability of herbaceous vegetation to deer, but the habitat quality of this landscape is still exceptional for deer.

These bucks were, after all, products of their environments, as nutritional limitations regulate what body size is optimal for the landscape and how many resources can be invested into secondary sexual characteristics, aka antlers. The limitations for each buck varied. While one may have been limited by important macro nutrients, another may have been limited by trace minerals. Without closely studying the diets and forage availability for each herd, it would be impossible to determine exactly which nutrients were limiting, but I hope it’s obvious from the photos and measurements that each buck was dealt a very different hand.

Just like antlers, the total body mass of deer is also affected by nutritional limitations. In fact, body mass and antler sizes are somewhat predictive of each other across regions. In our coastal example, mature bucks top out around 145 pounds on the hoof, whereas, according to the 2020 Indiana DNR White-tailed Deer Report, mature Indiana bucks weigh about 250 pounds on the hoof. The sensitivity of deer body weights to habitat quality has been well studied, which is why wildlife managers use metrics of body condition to evaluate relative habitat quality between local properties. You’ll notice that the included skull measurements are proportional to the antler sizes, just as the body weights of these deer would have also varied.

Incredible Adaptation

I would be remiss if I didn’t note that the three bucks I used for this comparison are individuals taken from much larger populations, and they do not represent the variation present within these populations. If you graph the antler sizes of bucks at any age class there will be a bell-shaped curve, where the most common antler size is in the middle and exceptionally large or small antlered deer are less common and represented by the small edges of the curve. The size of an “average” deer varies across regions due largely to environmental factors, as this article has described. However, wherever you are there is a chance that a truly exceptional buck could walk by you.

As we have reflected on the drastic differences among deer in the Midwest and Southeast, I encourage you to think about the spectacular adaptability this exemplifies in our beloved whitetails. They are capable of adapting to and thriving in a broad range of ecosystems and landscapes. Lindsay Thomas Jr. put it best in a recent article about whitetails in the fossil record: the whitetail, of all North America’s deer species extinct or living, is the most badass. I think this is an appropriate accolade for the whitetail. If you find yourself, like me, hunting southern whitetails that are comparable in size to large Labrador retrievers, take solace in the fact their smaller size compared to deer in other regions is not a sign they are inferior, it is a sign of superior adaptability!