If there are feral hogs in the woods you hunt, there may not be as many wild turkeys as there could be. Hogs have previously been named among many suspects for causing the recent national decline in turkeys, but not until this month did Auburn University reveal brand new science documenting a relationship: Where they exist in the U.S., feral hogs may be suppressing wild turkeys, and if you remove hogs, turkeys could rebound.

How hogs might hurt turkey populations is known from past research. When as much as 64% of a feral hog’s diet is mast, turkeys (and deer) are certainly affected. A study at the Caeser Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute at Texas A&M-Kingsville found 29% of simulated turkey nests were raided by hogs, the most of any nest predator. But no one had shown practical evidence that turkey numbers increase when hogs are controlled. At the International Wild Pig Conference on August 11, Matt McDonough of the Auburn University Deer Lab filled that gap.

“With the first post-removal survey in summer 2019, we were seeing a lot more adult birds on camera. I believe they had to have moved in from surrounding areas in response to the lower pig densities.”

From 2018 to 2021, Matt conducted an enormous study geared to look at long-term turkey poult production and overall population in response to feral hog removal, but he didn’t have to wait two or three years to start seeing results. After the first baseline turkey population survey in 2018 and the start of feral hog removals in May 2019, Matt and his co-researchers could see a change with their own eyes.

“We started seeing turkeys running around in a whole bunch of places we didn’t see them before,” Matt told me. “With the first post-removal survey in summer 2019, we were seeing a lot more adult birds on camera, too. This wasn’t part of my study, but I believe they had to have moved in from surrounding areas in response to the lower pig densities.”

Big Pig Study

As wildlife science goes, this was a “big” study. Matt had four separate study sites ranging from 6,100 to 13,500 acres, all located within 15 miles of each other, and each with feral hog densities representative of the broader region in Southeast Alabama (One of the four sites was the “control” where turkey populations were monitored but hogs were not removed, for comparison purposes). Camera surveys to estimate turkey populations were conducted repeatedly across the three years of the study using a grid system and a camera per 250 acres – yes, that’s a lot of cameras to check.

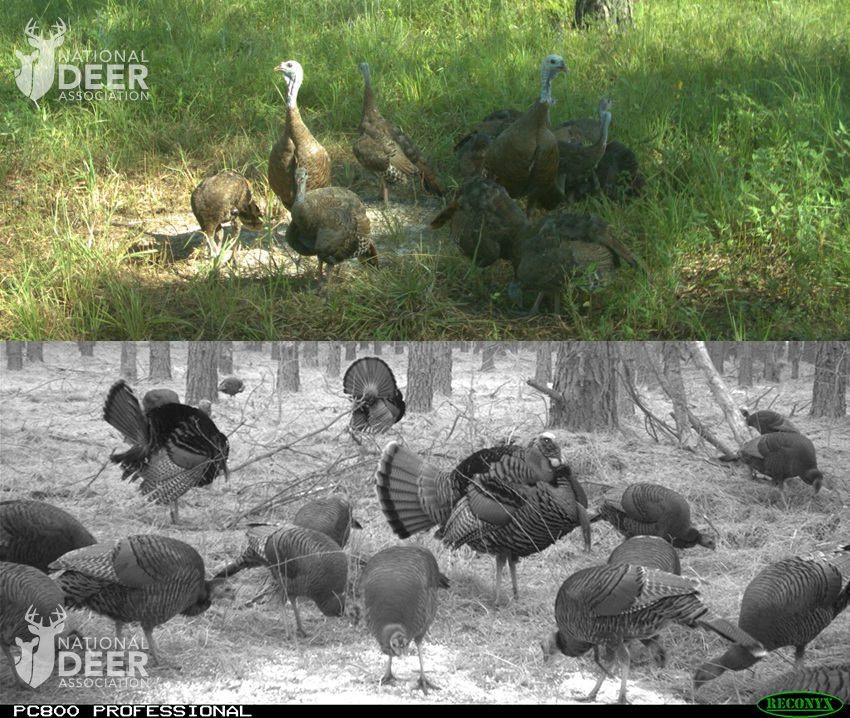

Matt McDonough of Auburn University used a grid network of baited trail-camera sites to estimate baseline feral hog populations on each of four study sites, before trapping began. This is an actual photo from the study.

To remove hogs on such big areas, Auburn had help from their co-researchers with USDA’s APHIS Wildlife Services. These professional trappers employed multiple styles of remote-triggered corral traps for whole-sounder removal, and on a few occasions they also shot hogs from helicopters. Matt initially estimated hog populations on each site with camera surveys, and then he measured removal levels throughout the study as a percentage of that initial population estimate. For example, USDA ultimately removed 657 hogs from Site 1, or 226% of the initial estimate – hogs can reproduce fast and migrate, so it was possible to kill more than 100% of the initial population estimate across the two years of removals. Site 2 saw 879 hogs removed (125%) and Site 3 saw 315 hogs removed (113%). Grand total: 1,851 hogs killed across two years of removal, a hog per 18 acres of treatment area. Matt said “complete eradication” of hogs was the goal, but they settled for “significant reduction.”

When the number of feral hogs removed is equal to the initial population, there will be a 70% increase in wild turkey abundance.

On two of the three pig-removal sites, the effect on turkey abundance and poult production across three years was significant. Sites 1 and 3 started equal with or below the “control” or non-removal area in turkey abundance but ended the three years far exceeding the control. Site 2 had the worst hog problem and saw the greatest removal (879 hogs), but removal success was slow to build until late in the study. Turkey abundance still climbed on Site 2 as hogs were removed, but the increase did not exceed that seen on the control site.

Crunching all these piles of numbers from camera surveys and pork, Matt made this statistically significant prediction if you trap hogs where you hunt:

“When the number of feral hogs removed is equal to the initial population, there will be a 70% increase in wild turkey abundance,” he said. “When you remove twice the initial hog population, there will be a 190% increase in wild turkey abundance.”

Matt also examined poult production separately from total turkey abundance. When the number of feral hogs removed is equal to the initial hog population, the probability of seeing turkey poults in the area is 3.5 times greater. When you remove twice the initial hog population, it’s 12.2 times greater.

Actual photos from later in Matt’s study, after hog removal efforts were underway. Matt saw turkey abundance as well as poult production climb significantly on two of three treatment sites.

Remember why Matt looked at hog removal as a percentage of “initial population” – because hog numbers, especially on average-sized hunting properties, are always fluctuating. Hogs are moving in and out across property lines. They’re breeding and producing new hogs. You’re never really done removing them in most areas where they are a problem. If you want to control hogs to help turkeys, don’t worry about calculating your own “initial population” estimate of hogs. Just hit them. As Matt’s study showed, putting a dent in their numbers, and continuing to hit them hard, could quickly affect turkey abundance.

What to Do

There are many good reasons to control or eradicate feral hogs where you hunt. If restoring turkey numbers is what motivates you, great. But understand you need to use the same hammer applied in Auburn’s study: whole-sounder removal through trapping. Sorry, but popping a few hogs from your deer stand this fall, or letting a buddy catch one with his dogs, ain’t gonna cut it. It feels good, but that’s not hog removal. With a reproduction rate six times that of whitetails – SIX TIMES – hogs don’t even flinch at random deer-season losses. You must remove at least 50 to 70% of a hog population annually, with most of those being sows and young, to bring them under control.

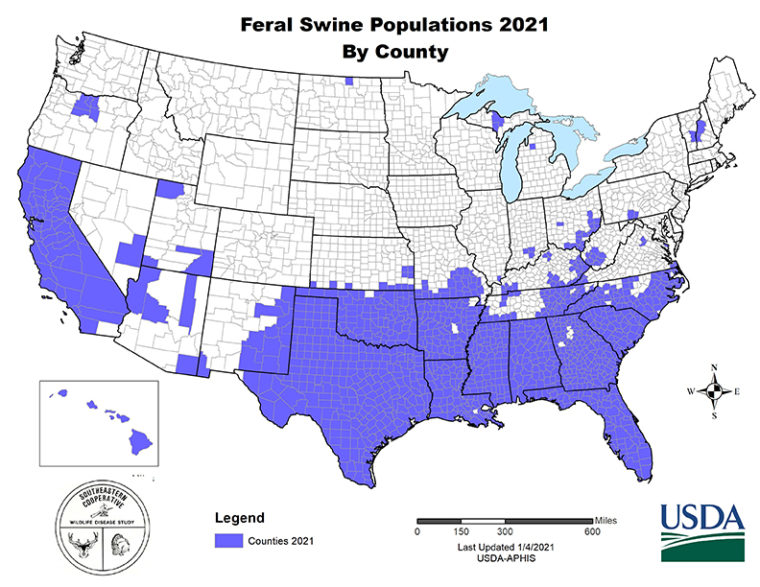

U.S. counties in blue on this map had “established” feral hog populations in a 2021 survey conducted by the Southeast Cooperative Disease Study and USDA.

Look into trapping for yourself, or contact a professional hog trapper near you. Numerous remote-triggered hog traps are available on the market, and I’ve personally experienced the effectiveness of the new Pig Brig trap design that is easy to use and very affordable. Watch the video review below.

“We can conclude wild hogs are affecting turkey populations in some fashion,” said Matt. “My study did not directly examine the why or how, but we can speculate based on previous research. As you reduce pig density, there should be less nest depredation. Plus, there will be more resources like acorns available to turkeys.”

Matt also emphasized his observation that adult turkey numbers seemed to climb immediately as hog density dropped, suggesting turkeys just don’t like to share space with hogs and will prefer your land where hogs are controlled.

Here, we can think like deer hunters, too. Reduced competition for acorns benefits deer as well as turkeys. We also know from previous research that deer do not like to share space with hogs. It follows that hog removal is good for deer and turkeys alike.

Just to be sure, deer are the focus of Phase 2 of Matt’s study. I’ll keep you posted.

For more research from the International Wild Pig Conference, NDA members will find a full report in the fall issue of NDA’s Quality Whitetails magazine.