In January, that somewhere is Alabama, Mississippi and parts of Louisiana. They’ll be rutting in the Florida panhandle into February or later. Even as you stand in your flip-flops cheering the Independence Day fireworks show, bucks will be working scrapes and checking does in south Florida.

In some locations in the South, the difference in rut peaks is a matter of state boundaries. Hunters in my home state of Georgia can hunt a November rut peak, like most deer hunters. Then they can drive across the state line into Alabama, buy a non-resident license, and hunt the rut again in January, with nothing more than a “Welcome to Alabama” sign between the two locations. And though many of these populations are no doubt exchanging genetics due to the short distances involved, the differences in rut timing have not changed for decades.

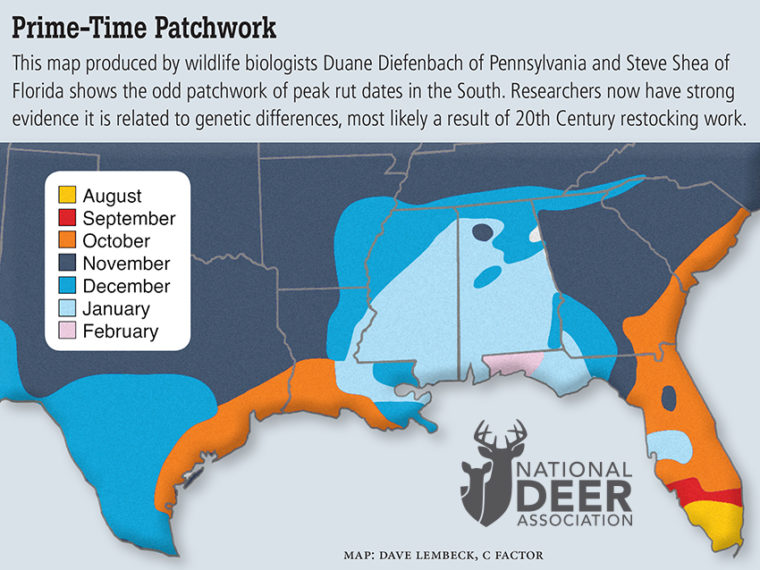

Many heads have been scratched over the odd mix of Southern rut peaks. In general, whitetail breeding dates range from narrow in the North – where fawns born outside a slim window in spring are not likely to survive their first winter – to broad in the tropics of Central America, where deer breed almost year-round because… they can. But from Texas to South Carolina, rut peak dates form a piebald pattern that doesn’t jive with the broader North American gradient (see the map below), and this has never been adequately explained. A common theory among biologists pointed to restocking efforts in the mid 1900s.

Jason Sumners, now the deer project leader for the Missouri Department of Conservation, decided to tackle this question for his master’s thesis while a graduate student at Mississippi State University. Suspecting that restocking efforts produced a fruit basket of deer genetics and associated rut peaks, Jason and his co-researchers selected pairs of deer populations in close proximity to one another but with widely varying rut peaks (a minimum of three weeks difference). Three of these pairs are in Mississippi, two in Louisiana, and one in Texas.

“These pairs of populations that are different are truly different,” Jason said. “In some cases, the early population will be done breeding before the late population starts, and they’re separated by less than 30 miles. You can’t explain it with differences in environmental conditions.”

As a control, they tested four additional pairs of populations that are close to each other but share similar rut peaks (all four of these are in Mississippi). DNA was then gathered and analyzed from all of the populations.

In studying the results, it was possible for the researchers to look at several layers of genetic relationships, including separate genetic markers passed along by bucks and does. On the buck side of the DNA, population pairs are very similar. Clearly, they are sharing genetics. Bucks are dispersing from both populations in each pair, as they typically do at 1½ years of age, and spreading their genes across the landscape.

“We see a tremendous amount of gene flow in terms of buck movement across the landscape,” Jason said. “But that exchange of bucks has not, through time, caused those breeding dates to converge.”

It is the doe side of the DNA, the genetics that all deer inherit from their mothers alone, where an explanation begins to emerge.

“When we looked at populations that have similar breeding dates, the maternal lineages are very similar,” said Jason. “When we looked at those close populations that have very different breeding dates, the maternal lineages are very different. Very, very different. The differences we observed are sub-species type differences.”

Unlike bucks that tend to disperse, does tend to be loyal to their birth range. Doe family groups often include several generations. So, genetic traits that are inherited primarily from the mother will move across a landscape very slowly, if at all. Jason’s results suggest that the genetic trigger for rut timing is maternally inherited. It is not spread by dispersing bucks, and that’s why the odd geographic differences have remained intact for decades – differences that are most likely a result of restocking.

The difficult part is tracing these genetic rut triggers back to their source populations. The trigger for does to come into estrus is photoperiod: the length of daylight hours. The specific day length that triggers the rut is unique to, and suited for, the historical geographic location where that population lives. If you move deer from that population to another geographic location, their ingrained genetic trigger continues to respond to the same day-length cue, but that particular day length is likely to be found on a different place in the calendar. On any given calendar day, the length of daylight varies widely by latitude. For example, pick a day in November and it will last more than an hour longer in Texas than in Minnesota. So, linking deer populations to their stocking sources is not simply a matter of matching calendar rut dates, because in all likelihood those calendar dates no longer match each other.

Only in the South would such transfers take hold. Deer with a photoperiod trigger that would fall early or late in the North would not produce fawns that would be likely to survive the existing climate conditions, so those genetics would be extinguished.

“Those environmental pressures that create the real synchronized rut that we have in the North don’t apply to the South,” said Jason. “The extreme seasonality of forage quality doesn’t exist, so whether they breed in November or January, it really doesn’t affect fawn survival.”

If you hunt in the South, your rut peak is what it is. It’s not likely to change except in a catastrophic situation like we faced in the 20th Century, in which deer were wiped out across large areas and replaced with new ones. Let’s all pray that never happens again.

Meanwhile, if you didn’t get enough of bucks chasing does, you don’t have to wait for November to return. You can always ring in the New Year in a more southerly deer stand!