Here are a few – amazingly not all – of the highlights I learned by attending the Southeast Deer Study Group meeting in February.

Important Note: Two additional new studies I learned about at this meeting, one testing the supposed benefits of mowing clover and another measuring aflatoxin contamination of deer corn, are featured in depth in the Summer 2021 issue of Quality Whitetails magazine. If you’re not an NDA member, you can still receive this issue if you join NDA by July 20!

60:40

The approximate buck:doe ratio for 71 fawns born to 56 does being tracked by Mike Muthersbaugh of Clemson University in South Carolina, for a fawn survival study. The first year, the buck:doe ratio of 39 fawns was 62:38, which is unusual because most studies show fawns born close to a 50:50 buck:doe ratio in healthy populations, and the study population appears to be in good nutritional condition. But the second year, the ratio was close to the same: 60:40 for 32 fawns. Whether this is just a result of a relatively small sample size or is a meaningful finding is unknown for now. Meanwhile, Mike found survival rates of around 31% each year for all of the fawns he was tracking. Not surprisingly, coyotes were the leading suspected cause of death among those fawns that did not survive. Mike won the award for best student poster presentation with this study, Clemson’s first student award in either the poster or live presentation category.

93 yards

Average distance between the two sides of a matched set of shed antlers, in a collection of 75 matched sets from the Platte River Valley of Nebraska. Brian Peterson of the University of Nebraska at Kearney also found the average distance was smaller for yearling bucks (59 yards)compared to bucks 2½ years olds or older (107 yards). 75% of yearling matched sets were found less than 5 yards apart while only 51% of matched sets from bucks 2½ years old or older were found less than 5 yards apart. Additionally, Brian determined peak antler-casting in the study area occurred between February 15 and March 15, with the earliest documented casting occurring in December and the latest in late April.

The kickoff of the 44th annual Southeast Deer Study Group meeting looked like an NDA event, with (clockwise from the bottom) Nick Pinizzotto, Kip Adams and Matt Ross welcoming attendees on the first day. But NDA was only a temporary host during the pandemic until state wildlife agencies can return to hosting in-person conferences in a rotation around 17 southeastern states.

94%

Proportion of the preferred deer forages – in open fields planted with native forb and grass mixtures – that was not a species in the planted seed mixture. Bonner Powell of the University of Tennessee compared several methods of converting fields dominated by tall fescue into productive deer cover and food. After killing the fescue, he tried six combinations of planting or not planting seed followed with fire, disking or mowing. While the value of these approaches varied in terms of the type of cover produced, planting seed wasn’t necessary to produce high-quality cover and abundant forage. Natural plant regeneration from the seedbank supplied a free source of that. Again, we see that quality deer habitat appears wherever we simply remove invasive plants and allow sunlight to do its work.

247 yards

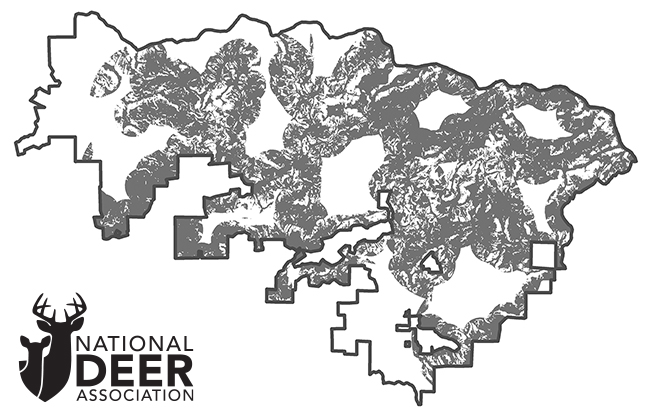

The average distance between hunters’ stands on Georgia public hunting land and the nearest road open to motor vehicles. Jackie Rosenberger of the University of Georgia Deer Lab used GPS to track 58 volunteer hunters on two north Georgia WMAs to study hunting pressure and deer movements. She found 90% of hunting pressure occurred on only 51% of the WMA land, with low or no hunting pressure on most of the remaining lands. Hunters preferred areas nearest to roads and avoided steep slopes, inadvertently creating deer sanctuaries in more remote and rugged areas. The map below is a graphic depiction of one of the WMAs in the study, with gray-colored areas within the WMA boundaries representing the area containing 90% of hunting pressure. White areas are hunted very lightly or not at all. Jackie’s study is part of a bigger UGA project looking at deer harvest and population declines on the Chattahoochee National Forest, where forest cover under 10 years of age now makes up less than 1% of the acreage.

Shaded areas inside this boundary map of a Georgia WMA represent land where 90% of hunting pressure was applied.

25,152

Increase in Pennsylvania’s general hunting license sales in 2020, the largest increase (3%) in almost 40 years, according to Bryan Burhans, executive director of the Pennsylvania Game Commission. Importantly, the increase was due in part to a jump in participation by young and new hunters. More than 25,000 new hunters age 12-34 bought a license for the first in Pennsylvania in 2020, the most since 2016. This matches trends seen in many other states in 2020: factors related to the pandemic and social distancing drove an increase in outdoor activities, especially hunting and fishing.

1911 to 1965

The years during which Kansas was considered a “deerless” state for whitetails and closed to whitetail hunting, according to Talesha Karish of Kansas State University. Following restoration, whitetails are now common in the Great Plains, expanding into the western two-thirds of the state that historically held only mule deer, and now displacing those mule deer. Whitetail survival, especially for does, is high. Of 90 does that Talesha collared and tracked beginning in 2018, only one was harvested by a hunter in 2018 and a second one in 2019.

47%

The reduction in woody tree saplings per acre by prescribed fire conducted in June compared to fire in March. If you’re trying to promote quality deer forage, this is a good thing, as woody species compete with more valuable forbs. Luke Resop of Mississippi State’s Deer Lab also measured a 200% increase in these forbs with a June fire. Traditional dormant-season fire still had its value, increasing some desirable species like blackberry compared to growing-season fire, and increasing forb growth compared to not burning at all. Luke’s advice based on his findings: “Diversify your fire timing.” Divide woods into multiple smaller units and burn some in the dormant season, some in the growing season, and some not at all.

5 out of 10

The number of deer that tested positive for chronic wasting disease (CWD) out of those killed by hunters on the 75-acre Wisconsin family farm of Mike Foy, a retired wildlife biologist with Wisconsin DNR (photos of two of the deer, both adult bucks, are seen below). The farm is in southeast Iowa County, on the edge of the core CWD infection area, a county that has an overall 28.5% infection rate among all deer (higher among bucks). Mike and his colleague Tom Hauge, also retired from Wisconsin DNR, spoke at the conference to urge other states to maximize their targeted removal efforts in CWD zones through engaging their hunters and landowners in the battle. Wisconsin DNR ended most of its targeted removal program in 2007, and CWD prevalence rates have worsened ever since. In states where it continues to be used, targeted removal is proving effective at holding prevalence rates at low levels across time in CWD zones.

Kelly Vanbeek arrowed this great Wisconsin buck on October 26 on Mike Foy’s Iowa County farm. When it tested positive for CWD, Wisconsin DNR issued Kelly a replacement tag. She arrowed another great buck (inset photo) on November 11. That buck also tested positive for CWD. They were among five deer out of 10 killed on a 75-acre farm last year that tested positive.

8

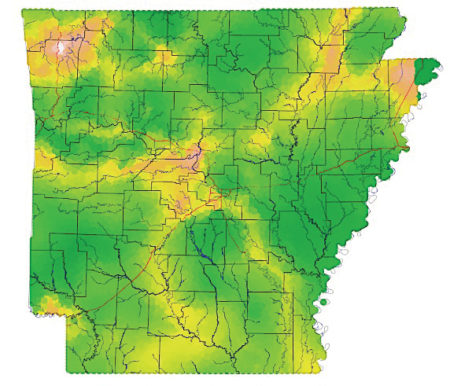

Number of major genetically distinct sub-populations of whitetails across the state of Arkansas. Tyler Chafin of the University of Arkansas collected DNA from 1,143 deer across the state and analyzed relatedness. Some of the groups are closely related but widely separated geographically, which correlates to restocking records of deer translocated within the state. Others result from natural recovery from small populations in refuge areas. Interestingly, one distinct population in southeast Arkansas is almost genetically indistinguishable from deer in Wisconsin, a restocking source for that area.

The map above shows Tyler’s results in color. Darker greens indicate deer populations that are closely related. Yellow to pink shades reveal less relatedness and are seen on this map as boundaries between the distinct groups, some of which lie along large rivers.

60 kcal/kg

The additional amount of digestible energy in deer browse and mast species at a site in South Texas that also has larger body and antler sizes compared to a second site. While kilocalories per kilogram is not a measurement you or I use when we talk about deer, what Seth Rankins of Texas A&M University-Kingsville learned in short is that available nutrition (in this case digestible energy and forage and browse diversity) explains more about regional differences in deer body and antler size than probably any other factor, like genetics. Congratulations to Seth, who won the award for best student presentation with this research. His advice? If you want larger body and antler sizes, work to increase the diversity of natural forages available where you hunt.